"The Boys King Arthur"

OF THE FAIR MAID OF ASTOLAT

The Boys King Arthur

by Sidney Lanier

Illustrated By N.C Wyeth

Each link is contans a few chapters from the book

You can change font color and background color at the top of the page

you can view Classics-illustrated.com on your smart tv using its browser.

The Boys King Arthur

BOOK VI

OF THE FAIR MAID OF ASTOLAT

SO after the quest of the Sancgreal was fulfilled, and all knights that were left on live were come again to the Table Round, then was there great joy, and in especial King Arthur and Queen Guenever made great joy of the remnant that were come home.And then the queen let make a dinner in London unto the knights of the Round Table. All at that dinner she had Sir Gawaine and his brethren, that is to say, Sir Agravaine, Sir Gaheris, Sir Gareth, and Sir Mordred. Also there was Sir Bors de Ganis, Sir Blamor de Ganis, Sir Bleoberis de Ganis, Sir Galihud, Sir Galihodin, Sir Ector de Mans, Sir Lionel, Sir Palamides, Sir Safere his brother, Sir La Cote Mal Taile, Sir Persartt, Sir Ironside, Sir Brandiles, Sir Kay le Seneschal, Sir Mador de la Porte, Sir Patrice, a knight of Ireland, [Sir] Aliduke, Sir Astomore, and Sir Pinel le Savage, the which was cousin to Sir Lamorak de Galis, the good knight that Sir Gawaine and his brethren slew by treason. And so these four and twenty knights should dine with the queen, and there was made a great feast of all manner of dainties. But Sir Gawaine had a custom that he used daily at dinner and at supper, that he loved well all manner of fruit, and in especial apples and pears. And therefore whosoever dined or feasted Sir Gawaine would commonly purvey for good fruit for him; and so did the queen for to please Sir Gawaine, she let purvey for him of all manner of fruit, for Sir Gawaine was a passing hot knight of nature. And this Pinel hated Sir Gawaine because of his kinsman Sir Lamorak de Galis, and therefore for pure envy and hate Sir Pinel enpoisoned certain apples, for to enpoison Sir Gawaine. And so this was well unto the end of the meat; and so it befell by misfortune a good knight named Patrice, cousin unto Sir Mador de la Porte, to take a poisoned apple. And when he had eaten it he swelled so till he burst, and there Sir Patrice fell down suddenly dead among them. Then every knight leaped from the board ashamed and enraged for wrath, nigh out of their wits. For they wist not what to say: considering Queen Guenever made the feast and dinner, they all had suspicion unto her.

"My lady, the queen," said Gawaine, "wit ye well, madam, that this dinner was made for me: for all folks that know my conditions understand that I love well fruit; and now I see well I had near been slain; therefore, madam, I dread lest ye will be shamed."

Then the queen stood still, and was sore abashed, that she wist not what to say.

"This shall not so be ended," said Sir Mador de la Porte, "for here have I lost a full noble knight of my blood, and therefore upon this shame and despite I will be revenged to the uttermost."

And thereupon Sir Mador appealed Queen Guenever of the death of his cousin Sir Patrice.' Then stood they all still, that none of them would speak a word against him, for they had a great suspection [suspicion] unto Queen Guenever, because she let make the dinner. And the queen was so sore abashed that she could none otherwise do but wept so heartily that she fell in a swoon. With this noise and sudden cry came unto them King Arthur, and marvelled greatly what it might be; and when he wist of their trouble, and the sudden death of that good knight Sir Patrice, he was a passing heavy man.

And ever Sir Mador stood still before King Arthur, and ever he appealed Queen Guenever of treason; for the custom was such at that time that all manner of shameful death was called treason.

"Fair lords," said King Arthur, "me repenteth sore of this trouble, but the cause is so we may not have to do in this matter, for I must be a rightful judge, and that repenteth me that I may not do battle for my wife, for, as I deem, this deed came never of her; and therefore I suppose we shall not all be destitute, but that some good knight shall put his body in jeopardy for my queen rather than she should be brent [burnt] in a wrong quarrel; and therefore, Sir Mador, be not so hasty, for it may happen she shall not be all friendless, and therefore desire thou the day of battle, and she shall purvey her of some good knight which shall answer you, or else it were to me great shame, and unto all my court."

1 We have here the beginning of that series of quarrels which

presently arrays Sir Gawaine and King Arthur (who with many

protests allows himself to be guided by Sir Gawaine) on one

side, against Queen Guenever and Sir Launcelot (who has taken

the queen's part) on the other, and which ends with the great

battle in which Arthur is slain and the Round Table broken up

for ever.

Then they answered by and by, and said they could not excuse the queen, for why she made the dinner, and either it must come by her or by her servants.

"Alas," said the queen, "I made this dinner for a good intent, and never for none evil; so Almighty God help me in my right."

"My lord the king," said Sir Mador, "I require you, as ye be a righteous king, give me a day that I may have justice." "Well," said the king, "I give the day this day fifteen days, that thou be ready armed on horseback in the meadow beside Westminster. And if it so fall that there be any knight to encounter with you, there mayest thou do the best, and God speed the right. And if it so fall that there be no knight at that day, then must my queen be burnt, and there shall she be ready to have her judgment." "I am answered," said Sir Mador; and every knight went where it liked him.

So when the king and queen were together, the king asked the queen how this case befell?

The queen answered, "So God me help, I wot not how, nor in what manner."

"Where is Sir Launcelot ?" said King Arthur, "and he were here, he would not grudge to do battle for you.

"Sir," said the queen, "I wot not where he is, but his brother and his kinsmen deem that he is not within this realm."

[For, within a little while before, it happened on a day that Queen Guenever was displeased with Sir Launcelot and forbade him the court, and that Sir Launcelot full sadly left the court and departed into his country and dwelt with the hermit Sir Brasias.]

"That me repenteth," said King Arthur, "for and he were here he would soon stint this strife. Then I will counsel you," said the king, "that ye go unto Sir Bors, and pray him to do that battle for you for Sir Launcelot's sake, and upon my life he will not refuse you; for right well I perceive that none of all these twenty knights that were with you in fellowship at your dinner will do battle for you: [which would be] great slander for you in this court."

"Alas !" said the queen, "I cannot do withal; but now I miss Sir Launcelot, for, and he were here, he would put me full soon unto my heart's ease."

"Now go your way," said the king unto the queen, "and require Sir Bors to do battle for you for Sir Launcelot's sake."

So the queen departed from the king, and sent for Sir Bors into her chamber; and when he was come, she besought him of succor.

"Madam," said he, "what would ye that I do? for I may not with my worship have to do in this matter, because I was at that same dinner, for dread that any of those knights would have me in suspection; also, madam," said Sir Bors, "now miss ye Sir Launcelot, for he would not have failed you, neither in right nor yet in wrong, as ye have well proved when ye have been in danger, and now have ye driven him out of this country, by whom ye and we all were daily worshipped.1 Therefore, madam, I greatly marvel me how ye dare for shame require me to do any thing for you, in so much as ye have chased him out of your country by whom we were borne up and honored."

"Alas! fair knight," said the queen, "I put me wholly in your grace, and all that is done amiss I will amend as ye will counsel me."

And therewith she kneeled down upon both her knees, and besought Sir Bors to have mercy upon her, "or I shall have a shameful death, and thereto I never offended." Right so came King Arthur, and found the queen kneeling afore Sir Bors. Then Sir Bors pulled her up, and said, "Madam, ye do to me great dishonor."

"Ah, gentle knight," said the king, "have mercy upon my queen, courteous knight, for I am now in certain she is untruly defamed. And therefore, courteous knight," said the king, "promise her to do battle for her; I require you, for the love of Sir Launcelot."

"My lord," said Sir Bors, "ye require me the greatest thing that any man may require me; and wit ye well, if I grant to do battle for the queen I shall wrath many of my fellowship of the Table Round; but as for that," said Bors, "I will grant my lord, for my lord Sir Launcelot's sake, and for your sake, I will at that day be the queen's champion, unless that there come by adventure a better knight than I am to do battle for her."

1 "Worshipped" made of worth, honored.

"Will ye promise me this," said the king, "by your faith ?""Yea sir," said Sir Bors, "of that will I not fail you, nor her both, but if that there come a better knight than I am, and then shall he have the battle."

Then was the king and the queen passing glad, and so departed, and thanked him heartily. So then Sir Bors departed secretly upon a day, and rode unto Sir Launcelot, there as he was with the hermit Sir Brasias, and told him of all their adventure.

"Ah," said Sir Launcelot, "this is come happily as I would have it, and therefore I pray you make you ready to do battle, but look that ye tarry till ye see me come, as long as ye may. For I am sure Mador is an hot knight, when he is enchafed, for the more ye suffer him, the hastier will he be to battle."

"Sir," said Sir Bors, "let me deal with him; doubt ye not ye shall have all your will."

Then departed Sir Bors from him, and came to the court again. Then was it noised in all the court that Sir Bors should do battle for the queen: wherefore many knights were displeased with him, that he would take upon him to do battle in the queen s quarrel, for there were but few knights in the court but they deemed the queen was in the wrong, and that she had done that treason. So Sir Bors answered thus unto his fellows of the Table Round: "Wit ye well, my fair lords, it were shame to us all, and we suffered to see the most noble queen of the world to be shamed openly, considering her lord and our lord is the man of most worship in the world, and most christened, and he hath ever worshipped us all, in all places."

Many answered him again: "As for our most noble King Arthur, we love him and honor him as well as ye do; but as for Queen Guenever, we love her not, for because she is a destroyer of good knights."

"Fair lords," said Sir Bors, "me seemeth ye say not as ye should say, for never yet in all my days knew I nor heard say that ever she was a destroyer of any good knight; but at all times, as far as I ever could know, she was always a maintainer of good knights, and always she hath been large and free of her goods to all good knights, and the most bounteous lady of her gifts and her good grace that ever I saw or heard speak of; and therefore it were great shame," said Sir Bors, "unto us all to our most noble king's wife, if we suffer her to be shamefully slain. And wit ye well," said Sir Bors, "I will not suffer it, for I dare say so much, the queen is not guilty of Sir Patrice's death, for she ought [owed] him never none evil will, nor none of the twenty-four knights that were at that dinner; for I dare well say that it was for good love she had us to dinner, and not for no mal engine [bad design], and that I doubt not shall be proved hereafter, for, howsoever the game goeth, there was treason among some of us."

Then some said to Sir Bors, "We may well believe your words."

And so some of them were well pleased, and some were not pleased.

The day came on fast until the even that the battle should be. Then the queen sent for Sir Bors, and asked him how he was disposed.

"Truly, madam," said he, "I am disposed in likewise as I promised you, [and I will not] fail you, unless by adventure there come a better knight than I to do battle for you; then, madam, I am discharged of my promise.

Then the queen went unto the king, and told him the answer of Sir Bors.

"Have ye no doubt," said the king, "of Sir Bors, for I call him now one of the best knights of the world, and the most profitable man."

And thus it passed on until the morn. And the king and the queen, and all manner of knights that were there at that time, drew them unto the meadow beside Westminster, where the battle should be. And so when the king was come with the queen, and many knights of the Round Table, then the queen was put there in the constable's ward, and a great fire made about an iron stake, that, and Sir Mador de la Porte had the better, she should be burnt. Such custom was used in those days, that neither for favor, neither for love, nor affinity, there should be none other but righteous judgment, as well upon a king as upon a knight, and as well upon a queen as upon another poor lady. So in this meanwhile came in Sir Mador de la Porte, and took his oath before the king, That the queen did this treason unto his cousin Sir Patrice, and unto his oath he would prove it with his body, hand for hand, who that would say the contrary. Right so came in Sir Bors, and said, that as for Queen Guenever, she is in the right, "and that will I make good with my hands, that she is not culpable of this treason that is put upon her."

"Then make thee ready," said Sir Mador, "and we shall prove whether thou be in the right or I."

"Sir Mador," said Sir Bors, "wit thou well I know you for a good knight: but I trust unto almighty God I shall be able to withstand your malice: but thus much have I promised my lord King Arthur, and my lady the queen, that I shall do battle for her in this case to the uttermost, unless that there come a better knight than I am, and discharge me."

"Is that all?" said Sir Mador; "either come thou off, and do battle with me, or else say nay.

"Take your horse," said Sir Bors, "and, as I suppose, ye shall not tarry long but that ye shall be answered."

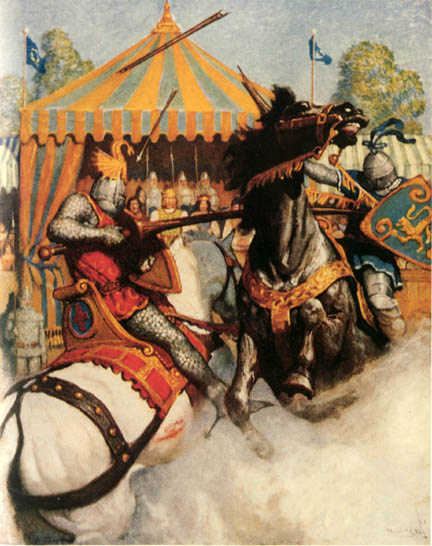

Then either departed to their tents, and made them ready to mount upon horseback as they thought best. And anon Sir Mador de la Porte came into the field with his shield on his shoulder, and a spear in his hand; and so rode about the place, crying unto King Arthur, "Bid your champion come forth, and he dare."

Then was Sir Bors ashamed, and took his horse, and came to the lists' end. And then was he ware where as came out of a wood, there fast by, a knight all armed at all points upon a white horse, with a strange shield, and of strange arms; and he came riding all that he might run; and so he came to Sir Bors, and said, "Fair knight, I pray you be not displeased, for here must a better knight -than ye are have this battle; therefore I pray you to withdraw you, for I would ye knew I have had this day a right great journey, and this battle ought to be mine, and so I promised you when I spake with you last, and with all my heart I thank you of your good will."

Then Sir Bors rode unto King Arthur, and told him how there was a knight come that would have the battle for to fight for the queen.

"What knight is he ?" said the king.

"I wot not," said Sir Bors, "but such covenant he made with me to be here this day. Now my lord," said Sir Bors, "here am I discharged."

Then the king called to that knight, and asked him if he would fight for the queen. Then he answered to the king, "Therefore came I hither, and therefore, Sir king," he said, "tarry me no longer, for I may not tarry. For anon as I have finished this battle I must depart hence, for I have ado many matters elsewhere. For wit you well," said that knight, "this is dishonor to you all knights of the Round Table, to see and know so noble a lady and so courteous a queen as Queen Guenever is thus to be rebuked and shamed amongst you."

Then they all marvelled what knight that might be that so took the battle upon him, for there was not one that knew him, but if it were Sir Bors. Then said Sir Mador de la Porte unto the king, "Now let me wit with whom I shall have ado withal."

And then they rode to the lists' end, and there they couched their spears, and ran together with all their mights. And Sir Mador's spear brake all to pieces, but the other's spear held, and bare Sir Mador's horse and all backward to the earth a great fall. But mightily and suddenly he avoided his horse, and put his shield afore him, and then drew his sword, and bade the other knight alight and do battle with him on foot. Then that knight descended from his horse lightly like a valiant man, and put his shield afore him, and drew his sword, and so they came eagerly unto battle, and either gave other many great strokes, tracing and traversing, raising and foining, and hurtling together with their swords, as it were wild boars. Thus were they fighting nigh an hour, for this Sir Mador was a strong knight, and mightily proved in many strong battles. But at last this knight smote Sir Mador grovelling upon the earth, and the knight stepped near him to have pulled Sir Mador fiatling upon the ground; and therewith suddenly Sir Mador arose, and in his rising he smote that knight through the thick of the thighs, that the blood ran out fiercely. And when he felt himself so wounded, and saw his blood, he let him arise upon his feet; and then he gave him such a buffet upon the helm that he fell to the earth flatling, and therewith he strode to him for to have pulled off his helm off his head. And then Sir Mador prayed that knight to save his life, and so he yielded him as overcome, and released the queen of his quarrel.

Sir Mado's spear brake all to pieces, but the other's spear held

"I will not grant thee thy life," said that knight, "only that thou freely release the queen forever, and that no mention be made upon Sir Patrice's tomb that ever Queen Guenever consented to that treason."

"All this shall be done," said Sir Mador, "I clearly discharge my quarrel forever."

Then the knights parters of the lists [knights who parted the combatants] took up Sir Mador and led him to his tent, and the other knight went straight to the stair foot whereas King Arthur sat, and by that time was the queen come unto the king, and either kissed other lovingly. And when the king saw that knight, he stooped down unto him and thanked him, and in likewise did the queen. And then the king prayed him to put off his helm and to rest him, and to take a sop of wine; and then he put off his helm to drink, and then every knight knew that he was the noble knight Sir Launcelot. As soon as the king wist that, he took the queen by the hand, and went unto Sir Launcelot, and said, "Gramercy of your great travel that ye have had this day for me and for my queen.

"My lord," said Sir Launcelot, "wit ye well that I ought of right ever to be in your quarrel, and in my lady the queen's quarrel, to do battle, for ye are the man that gave me the high order of knighthood, and that day my lady your queen did me great worship, or else I had been shamed. For that same day ye made me knight, through my hastiness I lost my sword, and my lady your queen found it, and lapped it in her train, and gave me my sword when I had need thereof, or else had I been shamed among all knights. And therefore, my lord King Arthur, I promised her at that day ever to be her knight in right or in wrong.

"Gramercy," said King Arthur, "for this journey; and wit you well," said King Arthur, "I shall acquit you of [repay you for] your goodness."

And ever the queen beheld Sir Launcelot, and wept so tenderly that she sank almost down upon the ground for sorrow, that he had done to her so great goodness, whereas she had showed him great unkindness. Then the knights of his blood drew unto him, and there either of them made great joy of other; and so came all the knights of the Round Table that were there at that time, and he welcomed them. And then Sir Mador was had to leechcraft [surgery]; and Sir Launcelot was healed of his wound. And then was there made great joy and mirth in the court.

And so it befell that the damsel of the lake, which was called Nimue, the which wedded the good knight Sir Pelleas, and so she came to the court, for ever she did great goodness unto King Arthur and to all his knights, through her sorcery and enchantments. And so when she heard how the queen was [endangered] for the death of Sir Patrice, then she told it openly that she was never guilty; and there she disclosed by whom it was done, and named him Sir Pinel, and for what cause he did it; there it was openly disclosed, and so the queen was excused, and the knight Sir Pinel fled into his country. Then was it openly known that Sir Pinel empoisoned the apples of the feast, to the intent to have destroyed Sir Ga- waine, because Sir Gawaine and his brethren destroyed Sir Lamorak de Galis, whom Sir Pinel was cousin unto.

And then Sir Mador sued daily and long to have the queen s good grace; and so, by the means of Sir Launcelot, he caused him to stand in the queen's grace, and all was forgiven. Thus it passed forth until our Lady Day the Assumption; within fifteen days of that feast King [Arthur let cry a great tournament] at Camelot, that is, Winchester, [where] he and the King of Scotland would, joust against all that would come against them. And when this cry was made, thither came many knights. So there came thither the King of Northgalis, and King Anguish of Ireland, and the king with the hundred knights, and Sir Galahalt the haut prince, and the King of Northumberland, and many other noble dukes and earls of divers countries. So King Arthur made him ready to depart to these jousts, and would have had the queen with him; but at that time she would not, she said, for she was sick and might not ride at that time.

"That me repenteth," said the king, "for this seven year ye saw not such a fellowship together, except at Whitsuntide when Galahad departed from the court."

"Truly," said the queen to the king, "ye must hold me excused: I may not be there, and that me repenteth."

And so upon the morn early Sir Launcelot heard mass, and brake his fast, and so took his leave of the queen, and departed. And then he rode so much until he came to Astolat, that is Gilford; and there it happed him in the eventide he came to an old baron's place, that hight Sir Bernard of Astolat. And as Sir Launcelot entered into his lodging, King Arthur espied him as he did walk in a garden beside the castle, how he took his lodging, and knew him full well.

"It is well," said King Arthur unto the knights that were with him in that garden beside the castle, "I have now espied one knight that will play his play at the jousts to the which we be gone towards, I undertake he will do marvels."

"Who is that, we pray you tell us," said many knights that were there at that time.

"Ye shall not wit for me," said the king, "at this time."

And so the king smiled, and went to his lodging. So when Sir Launcelot was in his lodging, and unarmed him in his chamber, the old baron came unto him, making his reverence, and welcomed him in the best manner; but the old knight knew not Sir Launcelot.

"Fair sir," said Sir Launcelot to his host, "I would pray you to lend me a shield that were not openly known, for mine is well known."

"Sir," said his host, "ye shall have your desire, for me seemeth ye be one of the likeliest knights of the world, and therefore I shall show you friendship. Sir, wit ye well I have two sons which were but late made knights, and the eldest high Sir Tirre, and he was hurt the same day that he was made knight, that he may not ride, and his shield ye shall have, for that is not known, I dare say, but here, and in no place else. And my youngest son hight Sir Lavaine, and if it please you he shall ride with you unto those jousts; and he is of his age strong and mighty, for much my heart giveth unto you that ye should be a noble knight, therefore I beseech you tell me your name," said Sir Bernard.

"As for that," said Sir Launcelot, "ye must hold me excused as at this time, and if God give me grace to speed well at the jousts, I shall come again and tell you; but I pray you heartily," said Sir Launcelot, "in any wise let me have your son Sir Lavaine with me, and that I may have his brother's shield."

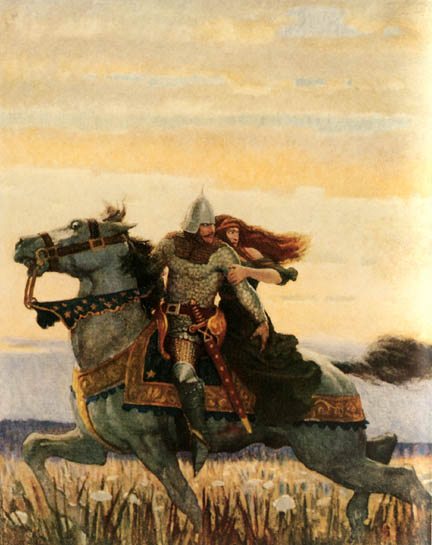

"Also this shall be done," said Sir Bernard. This old baron had a daughter that time that was called the fair maid of Astolat, and ever she beheld Sir Launcelot wonderfully; and she cast such a love unto Sir Launcelot that she could not withdraw her love, wherefore she died; and her name was Elaine la Blanche. So thus as she came to and fro, she besought Sir Launcelot to wear upon him at the jousts a token of hers.

"Fair damsel," said Sir Launcelot, "and if I grant you that, ye may say I do more for your love than ever I did for lady or damsel."

Then he remembered him that he would ride unto the jousts disguised, and for because he had never before that time borne no manner of token of no damsel, then he bethought him that he would bear one of hers, that none of his blood thereby might know him. And then he said, "Fair damsel, I will grant you to wear a token of yours upon my helmet, and therefore what it is show me."

"Sir," said she, "it is a red sleeve of mine, of scarlet well embroidered with great pearls."

And so she brought it him. So Sir Launcelot received it, and said, "Never or this time did I so much for no damsel."

And then Sir Launcelot betook [gave] the fair damsel his shield in keeping, and prayed her to keep it until he came again. And so that night he had merry rest and great cheer; for ever the fair damsel Elaine was about Sir Launcelot all the while that she might be suffered.

So upon a day in the morning, King Arthur and all his knights departed, for the king had tarried there three days to abide his knights. And so when the king was ridden, Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine made them ready for to ride, and either of them had white shields, and the red sleeve Sir Launcelot let carry with him. And so they took their leave of Sir Bernard the old baron, and of his daughter the fair maid of Astolat. And then they rode so long till that they came to Camelot, which now is called Winchester. And there was great press of knights, dukes, earls, and barons, and many noble knights; but there was Sir Launcelot privily lodged by the means of Sir Lavaine with a rich burgess, that no man in that town was ware what they were. And so they sojourned there till our Lady Day the Assumption, as the great feast should be. So then trumpets began to blow unto the field, and King Arthur was set on high upon a scaffold to behold who did best. But King Arthur would not suffer Sir Gawaine to go from him, for never had Sir Gawaine the better if Sir Launcelot were in the field. And many times was Sir Gawaine rebuked when Sir Launcelot came to any jousts disguised. Then some of the kings, as King Anguish of Ireland and the King of Scotland, were at that time turned upon King Arthur's side. And then upon the other side was the King of Northgalis, and the king with the hundred knights, and the King of Northumberland, and Sir Galahalt the haut prince. But these three kings and this one duke were passing weak to hold against King Arthur's party; for with him were the noblest knights of the world. So then they withdrew them either party from other, and every man made him ready in his best manner to do what he might. Then Sir Launcelot made him ready, and put the red sleeve upon his head, and fastened it fast; and so Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine departed out of Winchester privily, and rode until [unto] a little leaved wood, behind the party that held against King Arthur's party, and there they held them still till the parties smote together. And then came in the King of Scots and the King of Ireland on Arthur's party; and against them came the King of Northumberland; and the king with the hundred knights smote down the King of Northumberland, and also the king with the hundred knights smote down King Anguish of Ireland. Then Sir Palamides, that was on Arthur's party, encountered with Sir Galahalt, and either of them smote down other, and either party holp their lords on horseback again. So there began a strong assail upon both parties. And then there came in Sir Brandiles, Sir Sagramor le Desirous, Sir Dodinas le Savage, Sir Kay le Seneschal, Sir Griflet le Fise de Dieu, Sir Mordred, Sir Meliot de Logris, Sir Ozanna le Cure Hardy, Sir Safere, Sir Epinogris, and Sir Galleron of Galway. All these fifteen knights were knights of the Table Round. So these with more others came in together, and beat back the King of Northumberland, and the King of North Wales. When Sir Launcelot saw this, as he hoved in a little leaved wood, then he said unto Sir Lavaine, "See yonder is a company of good knights, and they hold them together as boars that were chafed with dogs."

"That is truth," said Sir Lavaine.

"Now," said Sir Launcelot, "and ye will help me a little, ye shall see yonder fellowship which chaseth now these men in our side, that they shall go as fast backward as they went forward."

"Sir, spare not," said Sir Lavaine, "for I shall do what I may."

Then Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine came in at the thickest of the press, and there Sir Launcelot smote down Sir Brandiles, Sir Sagramor, Sir Dodinas, Sir Kay, Sir Griflet, and all this he did with one spear. And Sir Lavaine smote down Sir Lucan le Butler, and Sir Bedivere. And then Sir Launcelot gat another spear, and there he smote down Sir Agravaine, Sir Gaheris, and Sir Mordred, and Sir Meliot de Logris. And Sir Lavaine smote down Ozanna le Cure Hardy: and then Sir Launcelot drew his sword, and there he smote on the right hand and on the left hand, and by great force he unhorsed Sir Safere, Sir Epinogris, and Sir Galleron. And then the knights of the Table Round withdrew them aback, after they had gotten their horses as well as they might.

"Oh, mercy," said Sir Gawaine, "what knight is yonder, that doth so marvellous deeds of arms in that field?"

"I wot what he is," said King Arthur, "but as at this time I will not name him."

"Sir," said Sir Gawaine, "I would say it were Sir Launcelot, by his riding and his buffets that I see him deal: but ever me seemeth it should be not he, for that he beareth the red sleeve upon his head, for I wist him never bear token, at no jousts, of lady nor gentlewoman."

"Let him be," said King Arthur, "he will be better known and do more or ever he depart."

Then the party that were against King Arthur were well comforted, and then they held them together, that before hand were sore rebuked. Then Sir Bors, Sir Ector de Mans, and Sir Lionel, called unto them the knights of their blood, as Sir Blamor de Ganis, Sir Bleoberis, Sir Aliduke, Sir Galihud, Sir Galihodin, Sir Bellangere le Beuse, so these nine knights of Sir Launcelot's kin thrust in mightily, for they were all noble knights. And they, of great hate and despite that they had unto him, thought to rebuke that noble knight Sir Launcelot, and Sir Lavaine, for they knew them not. And so they came hurtling together, and smote down many knights of Northgalis and of Northumberland. And when Sir Launcelot saw them fare so, he gat a spear in his hand, and there encountered with them all at once; Sir Bors, Sir Ector de Mans, and Sir Lionel smote him all at once with their spears.

And with force of themselves they smote Sir Launcelot's horse unto the ground; and by misfortune Sir Bors smote Sir Launcelot through the shield into the side, and the spear brake, and the head abode still in the side. When Sir Lavaine saw his master lie upon the ground, he ran to the King of Scotland and smote him to the ground, and by great force he took his horse and brought him to Sir Launcelot, and mauger [in spite of] them all he made him to mount upon that horse. And then Sir Launcelot gat him a great spear in his hand, and there he smote Sir Bors both horse and man to the ground; and in the same wise he served Sir Ector and Sir Lionel; and Sir Lavaine smote down Sir Blamor de Ganis. And then Sir Launcelot began to draw his sword, for he felt himself so sore hurt, that he wend there to have had his death; and then he smote Sir Bleoberis such a buffet upon the helm that he fell down to the ground in a swoon; and in the same wise he served Sir Aliduke and Sir Galihud. And Sir Lavaine smote down Sir Bellangere, that was the son of Sir Alisander Lorphelin. And by that time Sir Bors was horsed; and then he came with Sir Ector and Sir Lionel, and they three smote with their swords upon Sir Launcelot's helmet; and when he felt their buffets, and his wound that was so grievous, then he thought to do what he might whiles he might endure; and then he gave Sir Bors such a buffet that he made him to bow his head passing low; and therewithal he razed off his helm, and might have slain him, and so pulled him down. And in the same manner of wise he served Sir Ector and Sir Lionel, for he might have slain them. But when he saw their visages his heart might not serve him thereto, but left them there lying. And then after he hurled in among the thickest press of them all, and did there marvellous deeds of arms that ever any man saw or heard speak of. And alway the good knight Sir Lavaine was with him; and there Sir Launcelot with his sword smote and pulled down moe [‘more] than thirty knights, and the most part were of the Round Table. And Sir Lavaine did full well that day, for he smote down ten knights of the Round Table.

"Ah mercy, Jesu," said Sir Gawaine unto King Arthur, "I marvel what knight he is with the red sleeve."

"Sir," said King Arthur, "he will be known or he depart."

And then the king let blow unto lodging, and the prize was given by heralds to the knight with the white shield and that bare the red sleeve. Then came the king with the hundred knights, the King of Northgalis, and the King of Northumberland, and Sir Galahalt the haut prince, and said unto Sir Launcelot, "Fair knight, God thee bless, for much have ye done this day for us, therefore we pray you that ye will come with us that ye may receive the honor and the prize, as ye have worshipfully deserved it."

"My fair lords," said Sir Launcelot, "wit ye well, if I have deserved thanks, I have sore bought it, for I am like never to escape with my life; therefore I pray you that ye will suffer me to depart where me liketh, for I am sore hurt; I had liever [rather] to rest me than to be lord of all the world." And therewith he groaned piteously, and rode a great gallop away from them until he came to a wood side, and when he saw that he was from the field nigh a mile, that he was sure he might not be seen, then said he with a high voice, "0 gentle knight Sir Lavaine, help me that this truncheon were out of my side, for it sticketh so sore that it nigh slayeth me."

"0 mine own lord," said Sir Lavaine, "I would fain do that might please you, but I dread me sore, and I draw out the truncheon, that ye shall be in peril of death."

"I charge you," said Sir Launcelot, "as ye love me draw it out."

And therewithal he descended from his horse, and right so did Sir Lavaine, and forthwith Sir Lavaine drew the truncheon out of his side. And he gave a great shriek, and a marvellous grisly groan, and his blood brast [burst] out nigh a pint at once, that at last he sank down, and so swooned pale and deadly.

"Alas," said Sir Lavaine, "what shall I do ?" And then he turned Sir Launcelot into the wind, but so he lay there nigh half an hour as he had been dead. And so at the last Sir Launcelot cast up his eyes, and said, "0 Lavaine, help me that I were on my horse, for here is fast by within this two mile a gentle hermit, that sometime was a full noble knight and a great lord of possessions; and for great goodness he hath taken him to wilful poverty, and forsaken many lands, and his name is Sir Baldwin of Brittany, and he is a full noble surgeon, and a good leech. Now let see, help me up that I were there. For ever my heart giveth me that I shall never die of my cousin-german s hands."

And then with great pain Sir Lavaine holp him upon his horse; and then they rode a great gallop together, and ever Sir Launcelot bled that it ran down to the earth. And so by fortune they came to that hermitage, which was under a wood, and a great cliff on the other side, and a fair water running under it. And then Sir Lavaine beat on the gate with the butt of his spear, and cried fast, "Let in, for Jesu's sake."

And there came a fair child to them, and asked them what they would?

"Fair son," said Sir Lavaine, "go and pray thy lord the hermit for God's sake to let in here a knight that is full sore wounded, and this day tell thy lord that I saw him do more deeds of arms than ever I heard say that any man did."

So the child went in lightly, and then he brought the hermit, the which was a passing good man. So when Sir Lavaine saw him, he prayed him for God's sake of succor.

"What knight is he ?" said the hermit, "is he of the house of King Arthur or not ?"

"I wot not," said Sir Lavaine, "what is he, nor what is his name, but well I wot I saw him do marvellously this day, as of deeds of arms."

"On whose party was he ?" said the hermit.

"Sir," said Sir Lavaine, "he was this day against King Arthur, and there he won the prize of all the knights of the Round Table."

"I have seen the day," said the hermit, "I would have loved him the worse because he was against my lord King Arthur, for sometime I was one of the fellowship of the Round Table, but I thank God now I am otherwise disposed. But where is he? let me see him."

Then Sir Lavaine brought the hermit to him.

And when the hermit beheld him as he sat leaning upon his saddle-bow, ever bleeding piteously, [then] alway the knight hermit thought that he should know him, but he could not bring him to knowledge, because he was so pale for bleeding.

"What knight are ye," said the hermit, "and where were ye born?"

"Fair lord," said Sir Launcelot, "I am a stranger and a knight adventurous, that laboreth throughout many realms for to win worship."

Then the hermit advised him better [looked more closely], and saw by a wound on the cheek that he was Sir Launcelot.

"Alas !" said the hermit, "mine own lord, why hide ye your name from me? Forsooth I ought to know you of right, for ye are the most noble knight of the world, for well I know you for Sir Launcelot."

"Sir," said he, "sith ye know me, help me, and [if] ye may, for Christ's sake, for I would be out of this pain at once, either to death or to life."

"Have ye no doubt," said the hermit, "ye shall live and fare right well."

And so the hermit called to him two of his servants; and so he and his servants bare him into the hermitage, and lightly unarmed him, and laid him in his bed. And then anon the hermit stanched the blood; and then he made him to drink good wine; so by that Sir Launcelot was right well refreshed, and came to himself again. For in those days it was not the guise of hermits as it now is in these days, for there were no hermits in those days but that they had been men of worship and of prowess, and those hermits held great households, and refreshed people that were in distress.

Now turn we unto King Arthur, and leave we Sir Launcelot in the hermitage.

So when the kings were come together on both parties, and the great feast should be holden, King Arthur asked the King of Northgalis and their fellowship where was that knight that bare the red sleeve: "Bring him before me, that he may have his laud and honor and the prize, as it is right."

Then spake Sir Galahalt the haut prince and the king with the hundred knights: "We suppose that knight is mischieved, and that he is never like to see you, nor none of us all, and that is the greatest pity that ever we wist of any knight."

"Alas," said King Arthur, "how may this be? is he so hurt? What is his name

"Truly," said they all, "we know not his name, nor from whence he came, nor whither he would."

"Alas," said the king, "these be to me the worst tidings that came to me this seven year: for I would not for all the lands I hold, to know and wit it were so that that noble knight were slain."

"Know ye him?" said they all.

"As for that," said King Arthur, "whether I know him or know him not, ye shall not know for me what man he is, but Almighty Jesu send me good tidings of him."

And so said they all.

"By my head," said Sir Gawaine, "if it be so, that the good knight be so sore hurt, it is great damage and pity to all this land, for he is one of the noblest knights that ever I saw in a field handle a spear or a sword; and if he may be found, I shall find him, for I am sure that he is not far from this town."

"Bear you well," said King Arthur, "that ye may find him, without that he be in such a plight that he may not bestir himself."

"Jesu defend," said Sir Gawaine, "but I shall know what he is and if I may find him."

Right so Sir Gawaine took a squire with him, and rode upon two hackneys all about Camelot within six or seven mile; but as he went so he came again, and could hear no word of him. Then within two days King Arthur and all the fellowship returned to London again; and so as they rode by the way, it happened Sir Gawaine at Astolat to lodge with Sir Bernard, whereas Sir Launcelot was lodged. And so as Sir Gawaine was in his chamber for to take his rest, Sir Bernard the old baron came to him, and also his fair daughter Elaine, for to cheer him, and to ask him what tidings he knew, and who did best at the tournament at Winchester.

"So God help me," said Sir Gawaine, "there were two knights which bare two white shields, but the one of them bare a red sleeve upon his head, and certainly he was one of the best knights that ever I saw joust in field; for I dare make it good," said Sir Gawaine, "that one knight with the red sleeve smote down forty valiant knights of the Round Table, and his fellow did right well and right worshipfully."

"Now blessed be God," said the fair maid of Astolat, "that the good knight sped so well, for he is the man in the world the which I first loved, and truly he shall be the last man that ever after I shall love."

"Now, fair maid," said Sir Gawaine, "is that good knight your love?"

"Certainly," said she; "wit ye well he is my love."

"Then know ye his name ?" said Sir Gawaine.

"Nay, truly," said the maid, "I know not his name, nor from whence he came; but to say that I love him, I promise God and you that I love him."

"How had ye knowledge of him first ?" said Sir Gawaine.

Then she told him as ye have heard before, and how her father betook [intrmsted] him her brother to do him service, and how her father lent him her brother Sir Tirre's shield, "and here with me he left his own shield."

"For what cause did he so ?" said Sir Gawaine.

"For this cause," said the damsel, "for his shield was too well known among many noble knights."

"Ah, fair damsel," said Sir Gawaine, "please it you let me have a sight of that shield."

"Sir," said she, "it is in my chamber covered with a case, and if it will please you to come in with me ye shall see it."

"Not so," said Sir Bernard unto his daughter; "let send for it."

So when the shield was come, Sir Gawaine took off the case, and when he beheld that shield he knew anon that it was Sir Launcelot's shield, and his own arms.

"Ah Jesu, mercy!" said Sir Gawaine, "now is my heart more heavier than ever it was before."

"Why?" said the damsel Elaine.

"For I have a great cause," said Sir Gawaine; "is that knight that oweth that shield your love ?"

"Yea, truly," said she, "my love he is, God would that I were his love."

"So God me speed," said Sir Gawaine, "fair damsel, ye love the most honorable knight of the world, and the man of most worship."

"So me thought ever," said the damsel, "for never or that time for no knight that ever I saw loved I never none erst."

"God grant," said Sir Gawaine, "that either of you may rejoice other, but that is in a great adventure; but truly," said Sir Gawaine unto the damsel, "ye may say ye have a fair grace, for why I have known that noble knight this fourteen years, and never or that day I or none other knight, I dare make it good, saw nor heard that ever he bare token or sign of no lady, gentlewoman, nor maid, at no jousts nor tournament; and therefore, fair maid," said Sir Gawaine, ye are much beholden to give him thanks; but I dread me, said Sir Gawaine, "ye shall never see him in this world, and that is great pity as ever was of earthly knight."

"Alas!" said she, "how may this be? Is he slain?"

"I say not so," said Sir Gawaine, "but wit ye well that he is grievously wounded by all manner of signs, and by men's sight more likelier to be dead than to be alive, and wit ye well he is the noble knight Sir Launcelot, for by his shield I know him."

"Alas !" said the fair maid Elaine, "how may it be? what was his hurt ?" "Truly," said Sir Gawaine, "the man in the world that loveth him best hurt him so; and I dare say, and that knight that hurt him knew the very certainty that he had hurt Sir Launcelot, it would be the most sorrow that ever came to his heart."

"Now, fair father," said then Elaine, "I require you give me leave to ride and to seek him, or else I wot well I shall go out of my mind, for I shall never stint [stop] till that I find him and my brother Sir Lavaine."

"Do as it liketh you," said her father, "for me right sore repenteth of the hurt of that noble knight."

So the king and all came to London, and there Sir Gawaine openly disclosed to all the court that it was Sir Launcelot that jousted best.

So as the fair maid Elaine came to Winchester, she sought there all about, and by fortune Sir Lavaine was ridden to play him and to enchafe his horse. And anon, as fair Elaine saw him, she knew him, and then she cried aloud unto him; and when he heard her, anon he came unto her. And then she asked her brother, "How fareth my lord Sir Launcelot?"

"Who told you, sister, that my lord's name was Sir Launcelot?"

Then she told him how Sir Gawaine by his shield knew him. So they rode together till they came unto the hermitage, and anon she alighted; so Sir Lavaine brought her unto Sir Launcelot. And when she saw him lie so sick and pale in his bed, she might not speak, but suddenly she fell unto the ground in a swoon, and there she lay a great while. And when she was relieved, she sighed and said, "My lord Sir Launcelot, alas! why go ye in this plight ?" and then she swooned again. And then Sir Launcelot prayed Sir Lavaine to take her up and to bring her to him. And when she came to herself, Sir Launcelot kissed her, and said, "Fair maiden, why fare ye thus? Ye put me to pain; wherefore make ye no more such cheer for, and ye be come to comfort me, ye be right welcome, and of this little hurt that I have, I shall be right hastily whole, by the grace of God. But I marvel," said Sir Launcelot, "who told you my name.

Then the fair maiden told him all how Sir Gawaine was lodged with her father. "And there by your shield he discovered your name.

"Alas," said Sir Launcelot, "that me repenteth, that my name is known, for I am sure it will turn unto anger." So this maiden, Elaine, never went from Sir Launcelot, but watched him day and night and did such attendance to him that there was never woman did more kindlier for man than she did. Then Sir Launcelot prayed Sir Lavaine to make espies in WTinchester for Sir Bors if he came there, and told him by what token he should know him by a wound in his forehead.

"For well I am sure," said Sir Launcelot, "that Sir Bors will seek me, for he is the good knight that hurt me." Now turn we unto Sir Bors de Ganis, that came to Winchester to seek after his cousin Sir Launcelot. And so when he came to Winchester, anon there were men that Sir Lavaine had made to lie in watch for such a man, and anon Sir Lavaine had warning thereof. And then Sir Lavaine came to Winchester and found Sir Bors. And so they departed, and came unto the hermitage where Sir Launcelot was; and when Sir Bors saw Sir Launcelot lie in his bed all pale and discolored, anon Sir Bors lost his countenance, and for kindness and for pity he might not speak, but wept full tenderly a great while. And then when he might speak, he said unto him thus, "Alas! that ever such a caitiff knight as I am should have power by unhappiness to hurt the most noblest knight of the world. Where I so shamefully set upon you and overcharged you, and where ye might have slain me, ye saved me, and so did not I: for I, and your blood, did to you our uttermost I marvel that my heart or my blood would serve me, wherefore, my lord Sir Launcelot, I ask your mercy.

"Fair cousin," said Sir Launcelot, "I would with pride have overcome you all, and there in my pride I was near slain, and that was in mine own default, for I might have given you warning of my being there. Therefore, fair cousin," said Sir Launcelot, "let this speech overpass, and all shall be welcome that God sendeth; and let us leave off this matter, and let us speak of some rejoicing; for this that is done may not be undone, and let us find a remedy how soon that I may be whole."

And so upon a day they took their horses and took Elaine la Blanche with them; and when they came to Astolat, there they were well lodged and had great cheer of Sir Bernard the old baron and of Sir Tirre his son. And so on the morrow, when Sir Launcelot should depart, fair Elaine brought her father with her and her two brethren Sir Tirre and Sir Lavaine, and thus she said:

"My lord Sir Launcelot, now I see that ye will depart; fair and courteous knight, have mercy upon me, and suffer me not to die for your love."

"What would ye that I did?" said Sir Launcelot.

"I would have you unto my husband," said the maid Elaine.

"Fair damsel, I thank you," said Sir Launcelot; "but certainly," said he, "I cast me never to be married."

"Alas !" said she, "then must I needs die for your love."

"Ye shall not," said Sir Launcelot, "for wit ye well, fair damsel, that I might have been married and I had would, but I never applied me to be married; but because, fair damsel, that ye will love me as ye say ye do, I will, for your good love and kindness, show you some goodness, and that is this: that wheresoever ye will set your heart upon some good knight that will wed you, I shall give you together a thousand pound yearly to you and to your heirs; thus much will I give you, fair maid, for your kindness, and alway while I live to be your own knight."

"Of all this," said the damsel, "I will none, for, but if you will wed me, wit you well, Sir Launcelot, my good days are done."

"Fair damsel," said Sir Launcelot, "of [this] ye must pardon me."

Then she shrieked shrilly, and fell down in a swoon; and then women bare her into her chamber, and there she made overmuch sorrow. And then Sir Launcelot would depart; and there he asked Sir Lavaine what he would do.

"What should I do," said Sir Lavaine, "but follow you, but if ye drive me from you, or command me to go from you?"

Then came Sir Bernard to Sir Launcelot, and said to him, "I cannot see but that my daughter Elaine will die for your sake."

"I may not do withal," said Sir Launcelot, "for that me sore repenteth; for I report me to yourself that my proffer is fair, and me repenteth," said Sir Launcelot, "that she loveth me as she doth: I was never the causer of it, for I report me to your son, I early nor late proffered her bounty nor fair behests; and I am right heavy of her distress, for she is a full fair maiden, good, and gentle, and well taught." "Father," said Sir Lavaine, "she doth as I do, for since I first saw my lord Sir Launcelot I could never depart from him, nor nought I will and I may follow him."

Then Sir Launcelot took his leave, and so they departed, and came unto Winchester. And when King Arthur wist that Sir Launcelot was come, whole and sound, the king made great joy of him, and so did Sir Gawaine, and all the knights of the Round Table except Sir Agravaine and Sir Mordred.

Now speak we of the fair maiden of Astolat, that made such sorrow day and night, that she never slept, eat, nor drank; and ever she made her complaint unto Sir Launcelot. So when she had thus endured a ten days, that she feebled so that she must needs pass out of this world, then she shrived her clean, and received her Creator [took the Holy Communion]. Then her ghostly father bade her leave such thoughts. Then she said, "Why should I leave such thoughts? am I not an earthly woman? and all the while the breath is in my body I may complain me, for my belief is I do none offence though I love an earthly man, and I take God to my record I never loved none but Sir Launcelot du Lake, nor never shall. For our sweet Saviour Jesu Christ," said the maiden, "I take thee to record I was never greater offender against thy laws but that I loved this noble knight Sir Launcelot out of all measure, and of myself, good Lord, I might not withstand the fervent love wherefore I have my death."

And then she called her father Sir Bernard, and her brother Sir Tirre, and heartily she prayed her father that her brother might write a letter like as she would indite it. And so her father granted her. And when the letter was written word by word like as she had devised, then she prayed her father that she might be watched until she were dead, "And while my body is whole, let this letter be put into my right hand, and my hand bound fast with the letter until that I be cold, and let me be put in a fair bed with all the richest clothes that I have about me, and so let my bed and all my rich clothes be laid with me in a chariot to the next place whereas the Thames is, and there let me be put in a barge, and but one man with me, such as ye trust, to steer me thither, and that my barge be covered with black samite over and over. Thus, father, I beseech you let me be done."

So her father granted her faithfully that all this thing should be done like as she had devised. Then her father and her brother made great dole, for, when this was done, anon she died. And so when she was dead, the corpse and the bed and all was led the next day unto the Thames, and there a man and the corpse and all were put in a barge on the Thames, and so the man steered the barge to Westminster, and there he rowed a great while to and fro or any man espied it.

So by fortune King Arthur and Queen Guenever were speaking together at a window; and so as they looked into the Thames, they espied the black barge, and had marvel what it might mean.

Then the king called Sir Kay, and showed him it.

"Sir," said Sir Kay, "wit ye well that there is some new tidings."

"Go ye thither," said the king unto Sir Kay, "and take with you Sir Brandiles and Sir Agravaine, and bring me ready word what is there."

Then these three knights departed, and came to the barge, and went in; and there they found the fairest corpse lying in a rich bed that ever they saw, and a poor man sitting in the end of the barge, and no word would he speak. So these three knights returned unto the king again, and told him what they had found.

"That fair corpse will I see," said King Arthur. And then the king took the queen by the hand and went thither. Then the king made the barge to be holden fast; and then the king and the queen went in, with certain knights with them, and there they saw a fair gentlewoman lying in a rich bed, covered unto her middle with many rich clothes, and all was of cloth of gold; and she lay as though she had smiled. Then the queen espied the letter in the right hand, and told the king thereof. Then the king took it in his hand, and said, "Now I am sure this letter will tell what she was, and why she is come hither."

Then the king and the queen went out of the barge; and the king commanded certain men to wait upon the barge; and so when the king was come within his chamber, he called many knights about him, and said that he would wit openly what was written within that letter. Then the king brake it, and made a clerk to read it; and this was the intent of the letter: "Most noble knight, Sir Launcelot, now hath death made us two at debate for your love; I was your lover, that men called the fair maid of Astolat; therefore unto all ladies I make my moan; yet pray for my soul, and bury me at the least, and offer ye my mass-penny. This is my last request. Pray for my soul, Sir Launcelot, as thou art a knight peerless."

This was all the substance in the letter. And when it was read, the king, the queen, and all the knights wept for pity of the doleful complaints. Then was Sir Launcelot sent for. And when he was come, King Arthur made the letter to be read to him; and when Sir Launcelot heard it word by word, he said, "My lord Arthur, wit ye well I am right heavy of the death of this fair damsel. God knoweth I was never causer of her death by my willing, and that will I report me to her own brother; here he is, Sir Lavaine. I will not say nay, but that she was both fair and good, and much I was beholden unto her, but she loved me out of measure.

"Ye might have showed her," said the queen, "some bounty and gentleness, that might have preserved her life."

"Madam," said Sir Launcelot, "she would none other way be answered, but that she would be my wife, and of [this] I would not grant her; but I proffered her, for her good love that she showed me, a thousand pound yearly to her and to her heirs, and to wed any manner knight that she could find best to love in her heart. For, madam," said Sir Launcelot, "I love not to be constrained to love; for love must arise of the heart, and not by no constraint."

"That is truth," said the king, and many knights: "love is free in himself, and never will be bounden; for where he is bounden he looseth himself."

Then said the king unto Sir Launcelot, "It will be your worship that ye oversee that she be buried worshipfully."

"Sir," said Sir Launcelot, "that shall be done as I can best devise."

And so many knights went thither to behold the fair dead maid. And on the morrow she was richly buried; and Sir Launcelot offered her mass-penny, and all the knights of the Round Table that were there at that time offered with Sir Launcelot. And then when all was done, the poor man went again with the barge.

He rode his way with the queen unto Joyous Gard